"Changing the Future of Cities through Wood" Part 1—Nikken Sekkei(Takuya Oba) × VUILD (Koki Akiyoshi and Tatsuya Inoue)

Medium- and large-scale wooden construction and a timber supply infrastructure enabled by IT

Two-thirds of Japan's landmass is covered by forests. Approximately 40% of the area of Tokyo, the capital, is forest.

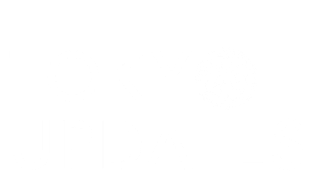

The trend towards the use of wooden in cities plays an important role not only as a countermeasure to global warming (*1), but also by relieving stress associated with urban life and by using wood to restore a healthy cycle between cities and forests. This in turn helps lead forests into a healthier state.

(*1) Achieving a carbon-neutral society requires not only reducing CO2 emissions. To that end, forests play a vital role in absorbing the remaining emissions. It then becomes critical to utilize the resulting timber to meaningful ends.

However, Japan's timber subsistence rate is 37.8% (2019) (*2) making it quite low, and this is out of balance with the growth rate of forests. Takuya Oba, a member of Nikken Sekkei, one of Japan's leading architectural design offices, launched the Nikken Wood Lab internally at the company as a way of driving this shift towards the use of wood in architecture and cities and responding to the growing crisis. For its part, VUILD is an architectural tech startup that is using digital technology to usher change to the architectural sector. Its CEO Hiroki Akiyoshi has a background in architecture, and COO Tatsuya Inoue has a background in forestry. With growing interest in a shift towards the use of wood in cities, how are these frontrunners using it in their work? What is the future of domestic timber, as well as architecture and cities?

(*2) Click here(P21) for the latest document in English(2018).

— Could you tell us what led to your shift in focus on this more active use of wood?

Oba: I was born and raised in an area of Fukuoka Prefecture where the majority of the population is 65 or older. The area was rich in nature and mountains. Living in the city, I wanted to find some way to get back to my roots and maybe create some feedback loop around resources that flow between local regions and urban centers. I realized that it came down to the use of wood.

— There has been a lot of interest in the large-scale wooden buildings Nikken Sekkei designed.

Oba: Legal reforms, and increasing momentum, have led to more active use of wood. In 2018, I launched the Nikken Wood Lab (hereafter "Wood Lab") internally at Nikken Sekkei. It was formally established as a department of the company in 2021. At Nikken Wood Lab, we engage in consulting and design around the use of wood in architecture.

— Was there a key change around the use of wood?

Oba: I would say that clients' stance towards it changed. While we might have pitched wooden buildings as eco-friendly to clients, they found the costs prohibitive. With the SDGs and ESG investment now becoming the norm, the tide has changed, and we have clients approaching us with projects involving wooden buildings. Deregulation is underway, with one factor aiding wooden construction being legal reforms to that end(Japanese only).

— VUILD has really taken the architectural industry by storm with its digital technology.

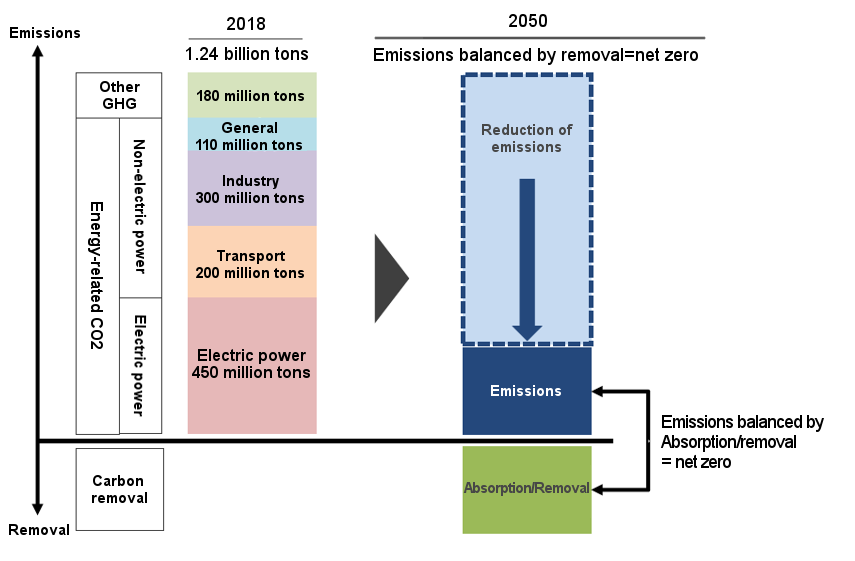

Akiyoshi: It all got started with the idea of, "What if we could make furniture or buildings as easily as we can use an iPhone?" We want to bring more equipment for digital machining to people around the world, and create contexts that allow regional operators to engage in craftsmanship without outside help. Specifically, we sold 74 3D wood processing machines—the ShopBot—to sawmills and construction shops in mountainous regions. Data can be sent right to the EMARF cloud service to order timber components directly from producers, just as you would with a printing service. In this way, we are creating infrastructure that will transform the supply chain.

#DYK about #DigitalFabrication? See how CEO AKIYOSHI Koki & his pioneering architectural tech startup @VUILDinc are harnessing advanced #ComputerDesign and #DigitalData to do everything online, helping everyone to build their dreams. https://t.co/1mH0ZKfp8t#NextGenJapan pic.twitter.com/NUsP6mDGAK

— The Gov't of Japan (@JapanGov) August 2, 2021

VUILD(Twitter:@JapanGov)

Inoue: Our goal is not simply bringing digital fabrication (using digital machining to form objects out of acrylic, wood or other materials using digital data) to a wider audience, but linking local regions with end-users and offering services that democratize craftsmanship.

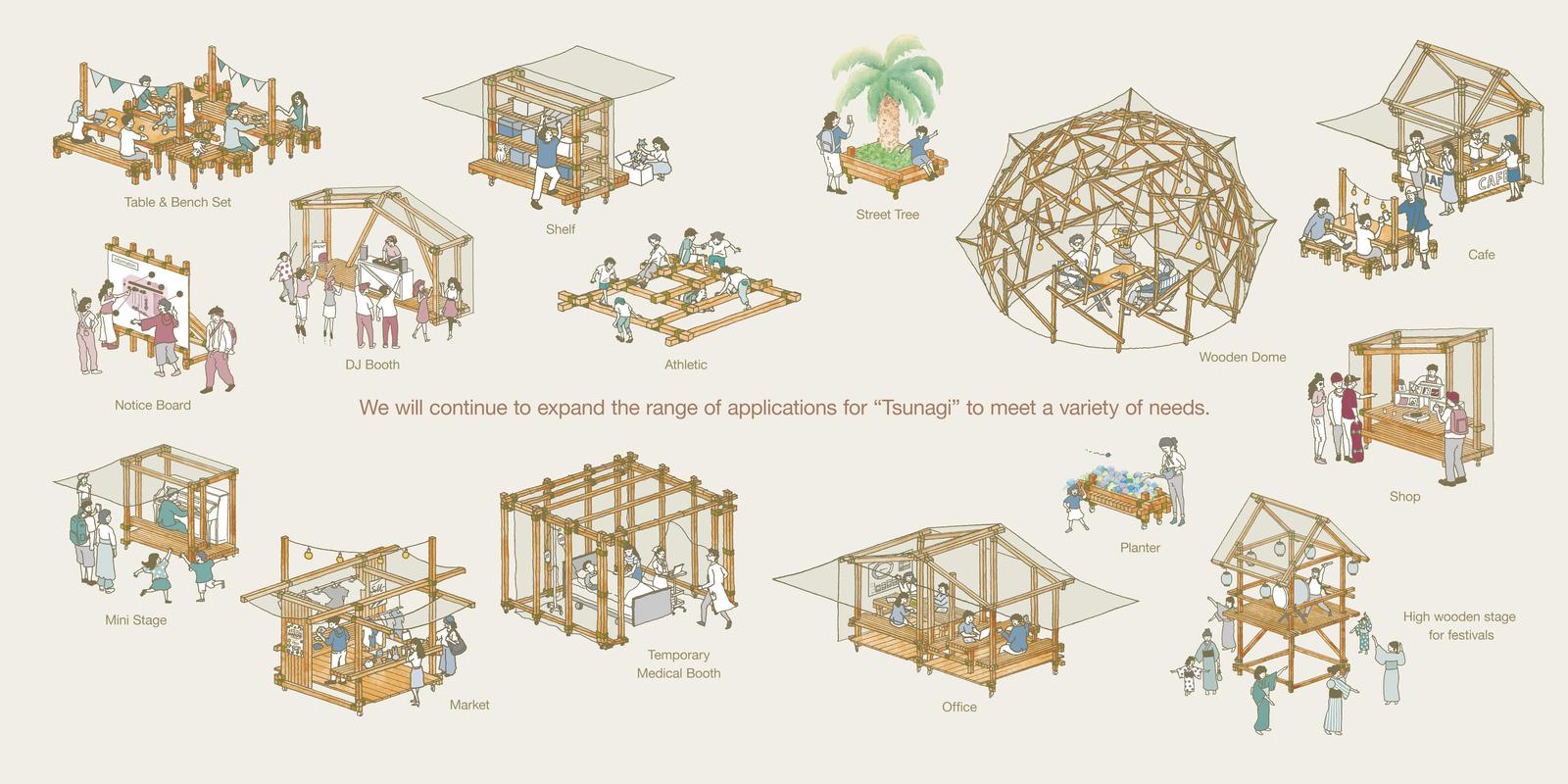

Oba: I, too, am exploring the possibilities of bringing added value to local society through craftsmanship. That is something we have in common with VUILD. At Wood Lab, we've developed an item called "Tsunagi'' (tsunagu = 'to connect' and gi = 'wood'), which uses mainstream timber and some proprietary metal fittings we developed to create modular units that can be configured into different forms. (Click on the image below to play the YouTube video). These can be used for COVID-19 contingent activities and as temporary shops in public spaces. Tsunagi make use of common wood cut lengthwise into standardized units. These units can be joined using a single ratchet fairly loosely. Even children can do it.

Oba: We want to not only use timber in medium- and large-scale structures [discussed in a later section], but to utilize projects like Tsunagi in order to expand the available options around wood use and to fundamentally advocate and encourage this use for wood.

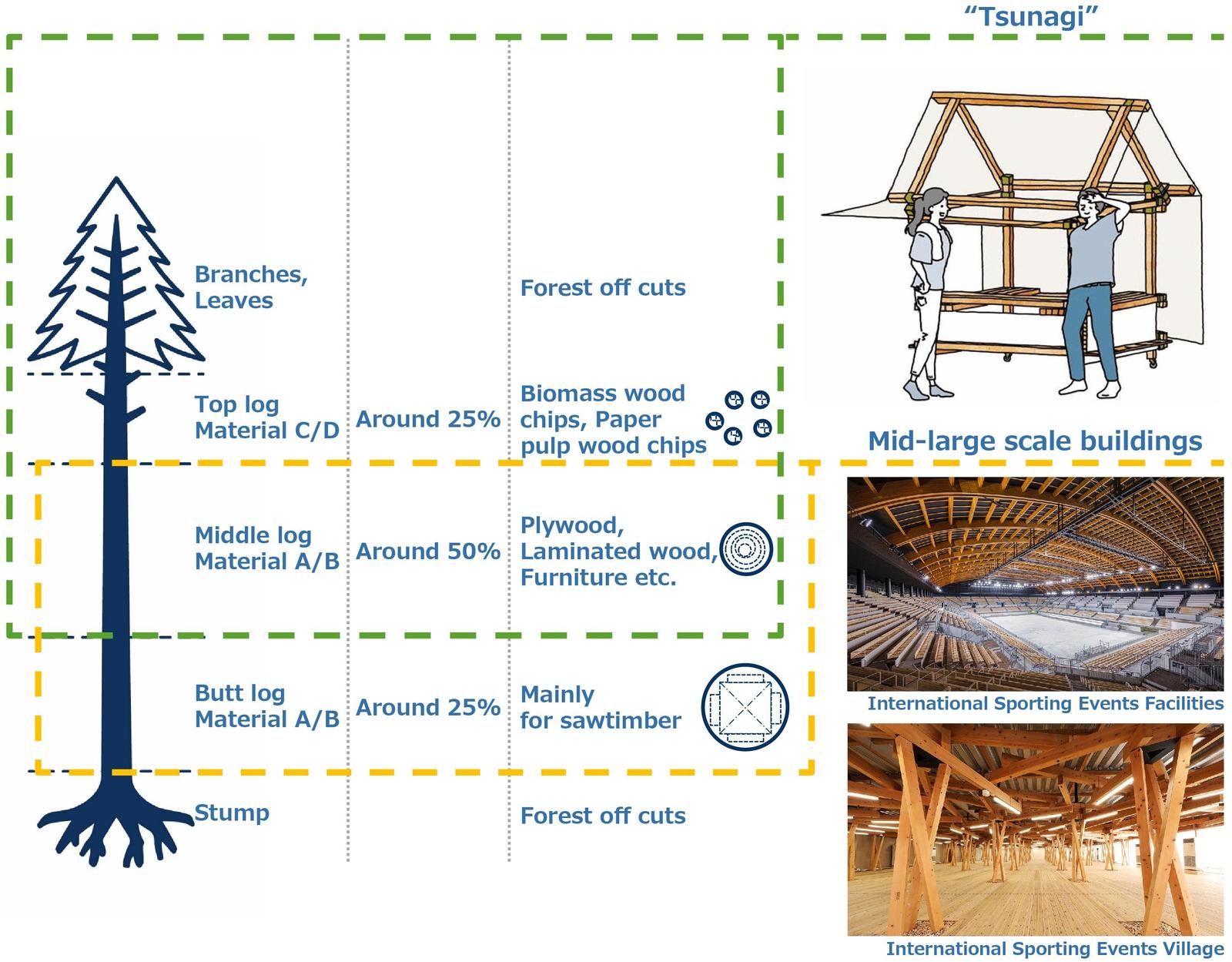

Substantively promoting the use of timber requires that it be thoroughly used in all kinds of contexts. While timber cut second and third closest to the root is often used in medium- and large-scale construction projects, Wood Lab wants to create alternative options for use of residual timber, such as through these Tsunagi units.

Substantively promoting the use of timber requires that it be thoroughly used in all kinds of contexts. While timber cut second and third closest to the root is often used in medium- and large-scale construction projects, Wood Lab wants to create alternative options for use of residual timber, such as through these Tsunagi units.Japan, where wood mileage is unsurpassed

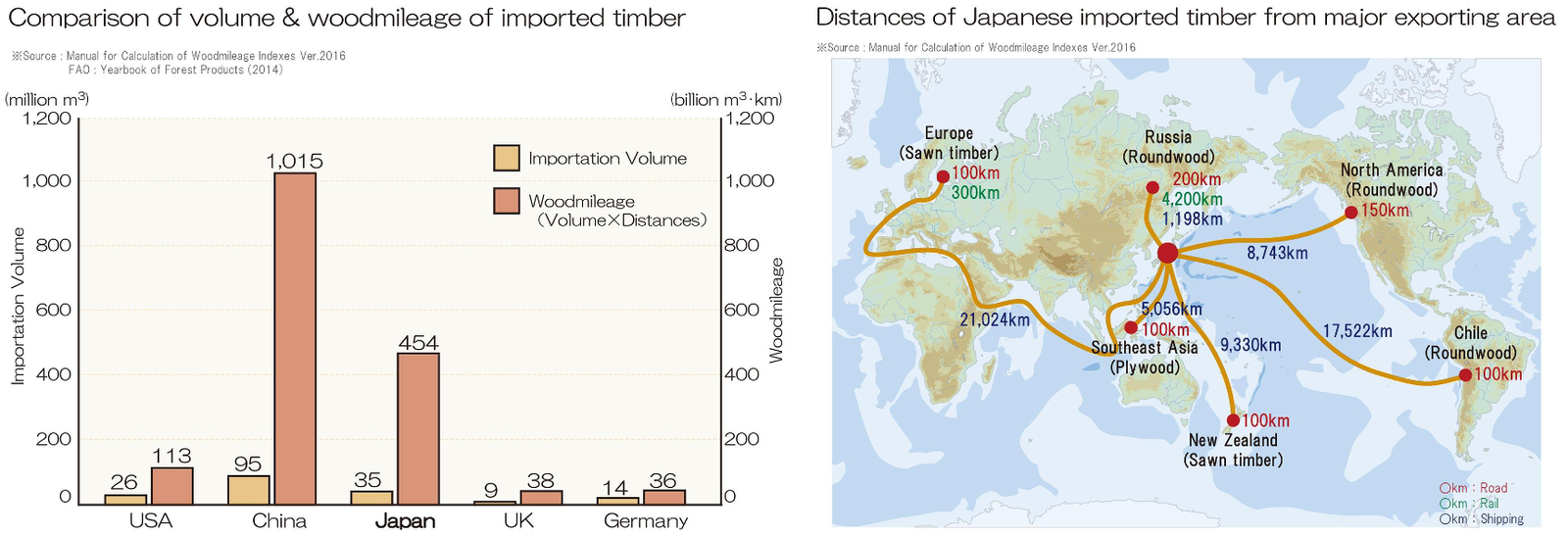

— We tend to have the sense that using wood is better for the environment, but how does the data look?

Oba: If the production of iron creates 100 units of CO2 emissions, plywood and other woods generate 0.3 units. Moreover, for wooden buildings, carbon storage is greater than carbon emissions during material production, so they are a net carbon negative. That said, Japan has a low rate of self-sufficiency at 37.8% (2019). Compared to other countries, "wood mileage" (a measure of the environmental impacts when transporting timber, calculated as the transportation distance from the wood production area to the consumption area multiplied by the amount of transported timber) is exceedingly high.

Source: The Woodmiles Forum's website

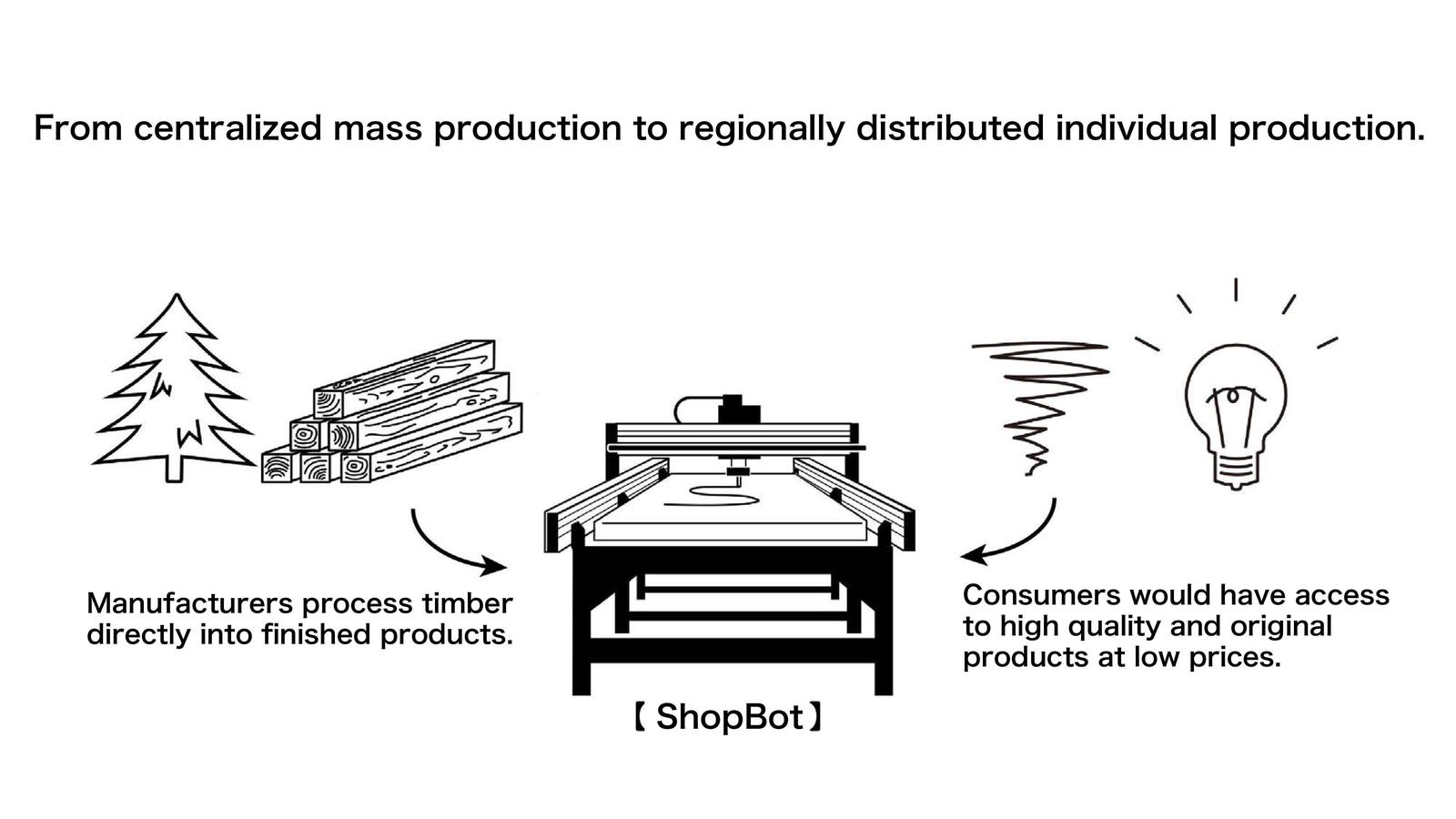

Source: The Woodmiles Forum's websiteAkiyoshi: We created the "House for Marebito (Marebito =a visitor from afar) " as a way of exploring to what extent we could reduce wood mileage. In a marginal settlement, we used the ShopBot wood processing machine and local wood to complete production entirely within the region. Our attempt to explore whether we could use this system to build houses using local timber resulted in a residential project in Akita Prefecture. We procure raw timber in the forests of Akita, and local clients use our system to build houses.

Oba: People often talk about driving money back into the forests, but it is quite challenging to do in practice.

Inoue: As Mr. Oba says, bringing back those funds to the mountains is no mean feat. In the first place, forestry depends on subsidies to survive as an industry, so there isn't much money to bring back to the mountains. Even if you have more logs in circulation, this may not vitalize the forestry industry or the local region itself. Therefore, we need to go beyond just cutting timber and onto ways of bringing added value to the forestry sector, such as through downstream, commercialized products.

VUILD's mission is to not only enrich the economy, but also to solve the question of how to lead better lives in these regions, and do so through technology.

— Would a lack of subsidies in turn force the forestry industry to vitalize itself?

Inoue: Without subsidies, it would cease to exist. That being said, simply relying on subsidies to resolve the bigger issues does not work.

Akiyoshi: Problematizing subsidies is not the best way of thinking about it. Forests are public, so thinking about them in a capitalist sense is not reasonable. That is why I was quite intrigued to see the forest transfer tax (a tax created to ensure that local financial resources needed to ensure forest management and promotion are allocated) come into being. Subsidies alone did not make sense as the only method of investing in the forests, after all. We have to shift forest management into being more of a public asset that each individual must feel responsible for investing in.

Inoue: We ran a simulation as follows. Supposing we used Japanese timber for just 1% of office floor space in Tokyo Prefecture's 23 wards, it would secure enough demand for thinning of forests in Nishiawakura in Okayama Prefecture—where I moved in order to work on vitalizing the local forestry industry and community-building projects—for a span of 50 years. Tokyo accounts for nearly 10% of all floor space in Japan, so shoring up those connections with local forestry would help support many regional economies and forestry industries. Tokyo is promoting a more active use of wood in buildings and interiors. I'd like to see them launch new investment schemes such as green bonds (bonds issued by companies and local governments to raise funds needed for green projects in Japan and overseas). That would create more opportunities for everyone to participate in a system for procuring timber in an environmentally-conscious fashion. I'd like to see subsidies not just around merely cutting timber, but around protecting the culture of forests.

Read more on: "Changing the Future of Cities through Wood" Part 2